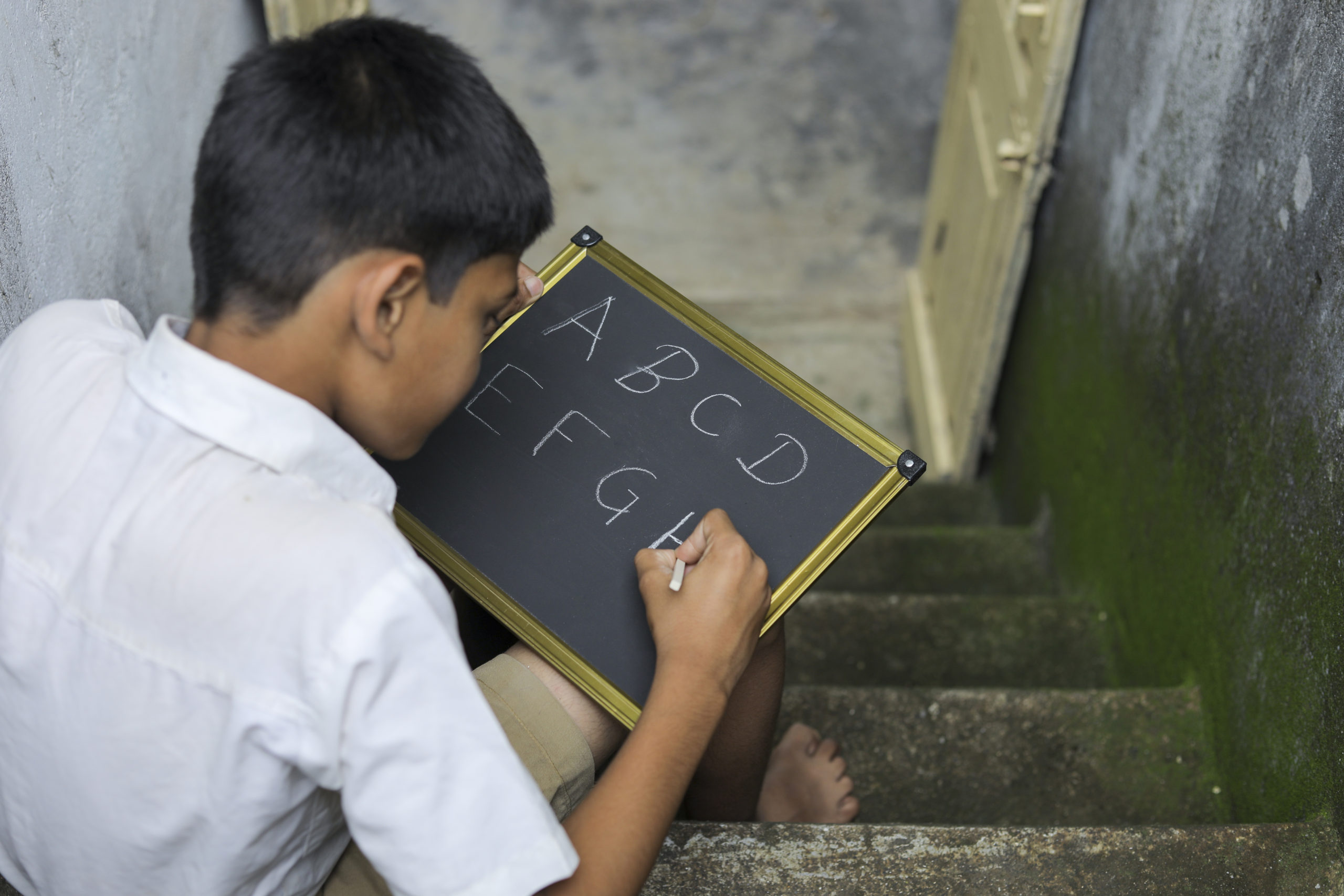

What are the realities and challenges of the NEP’s proposals to give Indian languages their place in the sun?

Divya Raj

Earlier this year, on July 29, 2020, the National Education Policy 2020 (NEP 2020) was approved by the Union Cabinet of India to replace the National Policy of Education of 1986.

In the few months that have followed, educators and other commentators have voiced their concerns on various aspects of the policy, with many focusing on the language-related guidelines that were proposed. Among other issues cited, critics have taken umbrage to a perceived political agenda to impose the learning of Hindi and Sanskrit on children from non-Hindi-speaking state and the sidelining of English in the overall scheme of things. There are some, however, who are cautiously optimistic about the recommendations, and some others who fully endorse them, citing as valid the policy’s justification that children between the ages of two and eight learn best in their mother tongues.

This article broadly explores some of the points outlined in the policy with regard to language teaching and learning and its use as a medium of instruction. At the macro-level, what does the overall thrust of the policy appear to be? At the teaching-learning level, how do we make sense of these points in terms of: a) administrative/practical decisions on implementation, and b) the realities

of students, parents, and teachers when it comes to languages – attitudes, aspirations, abilities, constraints, and so on?

Let us consider, to begin with, the policy seeking to lessen the importance given to English thus far in our school systems by replacing it with Indian languages as the medium of instruction. This begs the question, however: Can we can claim that despite the language occupying centre-stage all these

years, the majority of Indians are fluent in English today? One look around, even at those from supposedly ‘English-medium’ schools, tells us that this is clearly not the case. Poor learning outcomes across the board in all subjects indicate that quality teaching has not yet reached the masses of Indian students; this then, is clearly the core problem to be dealt with.

Why is it a problem that the majority of Indian students’ English language skills are so poor?

For one thing, however much the Draft NEP 2019 – the detailed report that explained the rationale behind the NEP 2020 – decried the “language of the colonists” and the “unnatural aspirations of Indian parents to concentrate on learning and speaking languages that are not their own”, it cannot be denied that parents will always seek greener pastures for their children and that English continues to serve as a passport to an economically brighter future. The policy highlights the successes of non-English- speaking global giants, presumably China, Japan, Germany and such countries but even in these countries, heavy investment in teaching and learning English continues. Also, as these countries have only one or a few official languages, as against the 22 scheduled languages in India, a comparison becomes irrelevant. In any case, these countries still number a handful; English-speaking behemoths such as the US, Canada, Australia, New Zealand and the UK, and some Asian countries

like Singapore remain preferred destinations for Indian students and professionals.

The other point to note here is that considering English a “foreign” language in India is just not realistic anymore. While it may be a bitter truth to swallow for some, the fact remains that our colonial past has spawned a generation of Indians tied to English as much as they are to the Indian languages they speak. For better or for worse, English has been woven into the fabric of Indian society more than merely as an ‘official’ language. A national education policy that hopes to turn the clock back is thus unrooted in present realities, in denial of India’s colonial past, and unmindful of the aspirations of young Indians who belong to a global world order.

Let us turn our attention to the policy’s thrust on “promoting multilingualism” through the revival of the three-language formula. That multilingualism and multiculturalism are integral facets of ‘Indianness’ is a given – the reality of everyday life in India illustrates this adequately enough. With more and more Indians from all strata of society moving around for work, many children across the country are

exposed to at least one other Indian language apart from their home language(s), besides English. So the policy envisaging that all children become literate and proficient users of not only their home languages, but the language of the state(s) they live in, of yet another Indian language, a classical Indian language, and English, in addition to other foreign languages of their choice, is like stating an obvious ideal for a child growing up in India. Why wouldn’t we all aspire to be polyglots and live such culturally well-rounded lives?

The relevant point to consider here, however, is whether it is realistic and reasonable to expect

schools to be the primary drivers of this lofty goal. As those involved in the nitty-gritty of imparting education in schools, particularly those with an understanding of language teaching and learning, it falls to us to reflect on how we can expect our under-funded schools, with huge challenges in recruiting and training teachers and handling disproportionately large numbers of students – who speak varied home languages – to develop the language skills of students in multiple languages. The

policy sidesteps the reality that a student’s academic year is already packed with a massive learning and examination load across all the subjects they study – where would there be the time to give language learning the attention it requires? Further, if English is denied its place as the medium of instruction until Class 8, it would be that much more of an uphill task to build English language skills at that late stage.

Given that languages are life skills, not merely academic tools, and that language learning

does not exist in a vacuum, the entire schooling system needs an overhaul in order to

achieve the ideals (even if we accept that they are desirable goals) outlined in the policy. The policy-drafters do acknowledge the enormity of the task on hand, but go no further with guidelines for implementation, leaving it to state governments, and ultimately school administrations to figure out how this is to be achieved.

Among the core transformations needed is the correction of the massively skewered bias towards

maths and science in our education system today. This policy, while paying lip service to the need for liberal arts education and the humanities, unfortunately continues to exhibit an indirect bias towards those who intend to pursue scientific careers, by emphasising that bilingualism in scientific learning (English plus an Indian language) is a worthy goal, as if to imply that this is not essential when it comes to other streams of study.

It is beyond the scope of this article to provide detailed implementation strategies, but broadly,

the quest to create a conducive environment for more effective learning (of languages, in particular) would ideally include a focus on:

• Upgrading teaching materials and incorporating them into the teaching process with more care

• Creating highly skilled and empathetic teachers who receive all the support they deserve and require

• Redesigning assessment processes so that they support learning rather than just being tedious administrative exercises that churn out a score against a child’s name in a report card

• Continuing to invest in developing students’ English language skills for all the reasons previously detailed, and also because many children still rely on schools as their primary source of English learning

The policy’s desire that Indian languages not suffer neglect in schools can certainly be taken

forward, as in any case, the overarching goal of education is to promote a respect for and interest in cultural differences. In practice, this can mean, for instance:

• Helping children learn English with support from the regional language in those cases where all students speak the same language

• English-speaking teachers having casual conversations with students in their mother tongue, to set them at ease

• Encouraging students to express things in their home language and finding ways to translate or explain this to others

• As the policy itself suggests, finding ways to expose students to other languages in Hindi- speaking states, where language diversity is lesser than, say, in South India, where media channels at least expose children to some bit of Hindi

• Ensuring that cinema and music in multiple Indian languages form a normal part of the school-going experience, and also that articles or discussions in English about Indian cultural entities such as movies, theatre and languages are harnessed as ways to reflect on different aspects of ‘Indianness’

The point here is that it essentially comes down to promoting an overall culture of respect,

curiosity and empathy – which are natural to most children anyway, when they feel comfortable and non-threatened. If these values underpin the attitudes of teachers and students in the classroom, as opposed to competitiveness, stress, and a pressure to teach and absorb knowledge forced on them

by the system, a respect for multilingualism is bound to develop organically, and one would not have to insist or mandate that students learn languages only in a formal manner.

Divya Raj has worked in the field of English language education for several years. She is a director at Syndrilla Education Support Services Pvt. Ltd. that offers customised English language learning solutions to individuals and organisations. With a background in ELT, Divya manages the company’s academic projects and is particularly interested in language acquisition in learners and in materials

development.