When teaching becomes an act of inquiry and exploration

Prerna Shivpuri

Have you seen a two-year-old with a toy car that he just received as a gift from someone? It’s a matter of minutes before the car is dismantled and pieces big and small fly in all directions. Why does a toddler do this? Have you ever wondered why most children take toys and household objects apart, open your drawers, your precious boxes and kitchen cupboards? They are the innate, natural curious learners that they are supposed to be at this age. This curiosity is our biggest asset as human beings and the basis of all our learning.

When children are curious, they are more likely to drive their own learning. Curiosity breeds initiative and independence. Curious learners actively seek out information/ solutions, taking more control of their learning. Several studies have made correlations between individuals who showed curiosity in a learning situation and long-term, more accurate memory of what was learned. “When students are curious about something, they seek an explanation. This motivates them to persevere in seeking information. They now WANT to learn, what they need to be taught.”(Willis 2010)

So what implications does this have for our teaching? How do we make sure that our students remain curious to learn and willingly engage with content? For that, we ourselves have to be curious as educators. We need to model great questioning in the classrooms that inspires them to ask more questions and ignite a desire to find out more about the world.

“Somewhere between ages 4 and 5, children are ideally suited for questioning: They have gained the language skills to ask, their brains are still in an expansive, highly-connective mode, and they’re seeing things without labels or assumptions. They’re perfect explorers.”

Ron Berger: A more Beautiful Question

Ask open-ended questions

Often, the teachers’ questioning is limited to subject content and facts. They pose questions that are more close-ended and typically have one right answer. We need to move away from this paradigm and start asking more open-ended questions that invite multiple perspectives, diverse answers and open up several lines of inquiry in the students’ minds. It’s only then that the student will develop a

quest for knowing and learning and a desire to dig deeper. As educators model great open-ended questioning, it builds questioning skills in the learners and takes them towards higher order thinking.

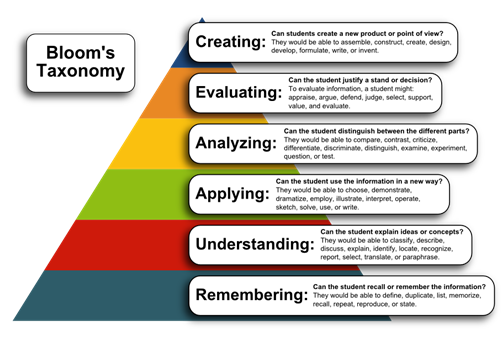

If you look at the given diagram of Bloom’s taxonomy, you will find that close-ended questioning makes learners remain at the bottom of the pyramid. It is all about memorising and remembering facts. On the other hand, as they go up the pyramid, it takes them to the higher cognitive functions of

analysis, judgement, comparing, critiquing, designing and so on. These higher order thinking skills are the ones every workplace in the world looks for in their employees and we need to build them step by step in our classrooms. Our students need to experience and practise these skills enough and build

great cognitive capacity right from childhood so that these qualities become second nature when they step into the workforce.

Let’s look at some of the ways we can design open-ended questions that would make teaching and learning a process of inquiry and exploration and would be a complete joy for learners as well as teachers.

Guiding Questions

These questions connect with big ideas, concepts and phenomena. Good guiding questions are like overarching ideas that open up various layers of knowledge. They make the students think and wonder and set them off on an inquiry. They provide room for research on associated topics and concepts and will invite multiple perspectives rather than one correct answer. Using good guiding questions at the beginning of a topic or concept is useful as it provides direction for students to investigate it, find and collect data rather than have the teacher give them the facts. Some examples of good guiding questions are: ”Where did the ancient Egyptians come from?” and “Where did they

go?”, “What is waste?” “Where do waves come from?” “What is worth fighting for?” “When are laws fair?”

Probing Questions

These questions are narrower than guiding questions and make students think further about the topic. They challenge the existing understanding of students and nudge them to use higher order thinking to reach the conclusions. These questions push the students to analyse, compare and contrast, defend their arguments and give more direction to their thinking so that they construct their own understanding and connect it with the subject of study.

Some examples of good probing questions are: “Why does a small iron nail sink in water while a huge ship floats on the ocean?” “What happens when you put an ice cube into a warm drink on a summer day?” “How is the life cycle of a butterfly similar to and different from yours?” Notice that these questions are slightly more specific and invite the students to present their reasoning and supporting evidence.

Probing questions are very useful to understand students’ misconceptions and work with them as we go further in our inquiry. These are still fairly open-ended and not pointing towards any one answer. Rather, they are helping students to observe, investigate, experiment, connect different concepts, clarify their notions and present their findings. These are very effective in the middle of the topic or unit, after you have put forth the guiding question and have had the students work on the topic for a while. At this stage, we are trying to give a boundary to their research and help them make

connections to reach certain conclusions and understandings.

Leading Questions

These questions are very narrow and often have answers of a limited range. We use leading questions at the end of a topic or unit and sometimes in between when we are trying to gauge the students’ depth of understanding. These questions usually have a pre-determined answer. Very often, leading questions have the answer hidden inside them and thus drive the thinking of the students. These can be useful while we are in a discussion with them and asking them probing questions to investigate.

A leading question in such a discussion might re-direct their thinking and help them go to the

next level of inquiry. However, these should be used sparingly as they do not really probe students’

thinking. Some examples of leading questions are: “Should species be allowed to go extinct?”

“Why is Brand X better than Brand Y?” “What is the function of chlorophyll in the process of

photosynthesis?” “Should waste be recycled?” and so on. You will notice that some of them have

obvious answers and a restricted range of inquiry. One thing that might make leading questions

more useful is adding “Why?” after them. This might stretch students’ thinking and invite arguments,

clarifications and reasoning.

Inquiry Question

Look into your lesson plans or pick any one lesson that you have done recently. Do an auditing of

your plan based on the three kinds of questions discussed above. Reflect on how your lesson went and what kind of questions you asked. Recollect how the students responded. Now try to frame some guiding and probing questions that might have invited more inquiry and investigation and think how students would have benefited from this process.

Try a Tip

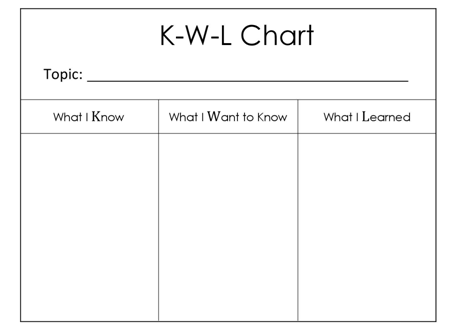

One of the tools used most widely to encourage questioning on the part of the student is the KWL

chart. We typically use it at the beginning of a unit. It asks students to put down what they Already Know about an existing topic and then they can write what they wonder or what they Want to Know in that topic. After this the teacher engages them in a series of investigation using guiding and probing questions and at the end or sometimes even in between, the students pen down their Learning in the Learned section of the table.

Prerna Shivpuri is Academic Head; I Am A Teacher, Mumbai. IAAT, a not-for-profit organisation, is committed to building a model of excellence for teacher education in India.

www.iamateacher.in