The PISA test evaluates the quality, equity and efficiency of school education systems across much of the world and can affect education policies and outcomes

Team TLT

Early December saw the release of the PISA results. PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) is a test that measures 15-year-olds’ ability to use their reading, mathematics and science knowledge and skills to meet real life challenges. It is conducted by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) every three years. The results have a significant impact on the way education is practised across much of the globe.

It was first conducted in 2000 and has been held every three years. Its aim is to assess the quality, equity and efficiency of school systems and provide comparable data so that countries can improve their education policies and outcomes.

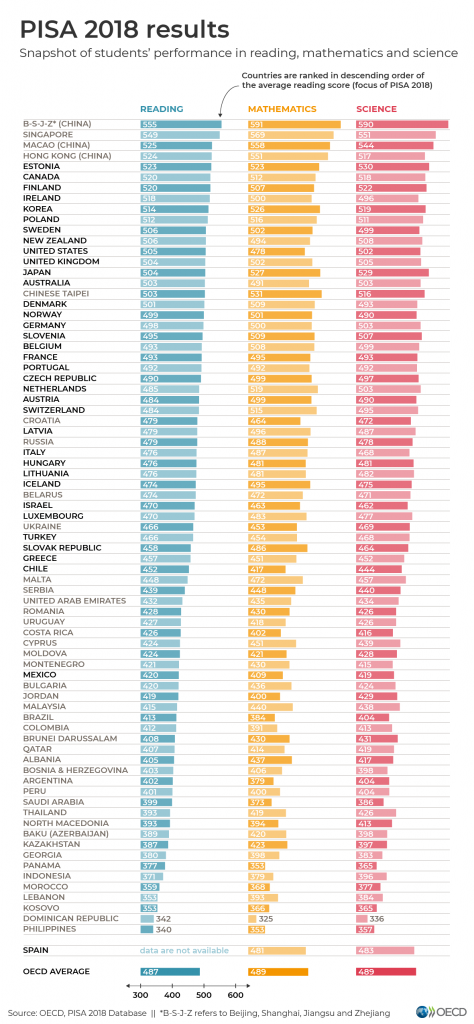

The OECD’s PISA 2018 tested around 600,000 students in 79 countries and economies in reading, science and mathematics. The main focus was on reading, with most students doing the test on computers.

Schools in countries that are OECD members as well as non-members can take the test. Application of findings from the results data can have an effect on the knowledge imparted in schools, change assessment policies and influence national education policies. Stung by “PISA shocks”, many countries have introduced new curricula. These include Norway, Denmark, Germany Sweden and Japan. New national standards and modes of testing have been introduced.

PISA test questions do not measure how well the student can reel off theories and principles but examine whether they employ that knowledge and apply it to life in the real world. “If they learn how to learn, and are able to think for themselves, and work with others, they can go anywhere they want,” says a statement on the PISA website.

India and PISA: After a gap of over a decade, India will be participating in PISA in 2021. It was in 2009 that India participated in PISA. It fared badly then, standing 72nd among 74 participating countries.

Announcing the 2021 participation last year, Rina Ray, then Secretary, Department of School Education and Literacy, HRD Ministry, said, “If 80 countries can participate in PISA, including China and Vietnam, then there is no reason why children in India cannot appear for it.”

According to her, India would apply with Chandigarh-based Kendriya Vidyalayas, Navodaya Vidyalayas and all schools private and government for the 2021 test. The application process takes three years.

Rules and regulations: PISA is conducted online, and takes about three hours. It assesses students between the ages of 15 years and 3 months and 16 years and 2 months, and who are enrolled in an educational institution at Grade 7 or higher.

PISA uses multiple-choice testing as the main feature of its assessments because “it is reliable, efficient, and supports robust and scientific analyses”. Typically, up to one-third of questions in a PISA assessment are open-ended. Participating countries and economies submit questions that are added to items developed by the OECD’s experts and contractors. The questions are reviewed and checked for cultural bias. Only those questions that pass these checks are used in PISA. There is a trial test run in all participating regions.

All students do not receive the same set of questions. The PISA test is designed to provide an assessment of performance at the system (or country) level, not for individual students. From previous years’ results, Asian education systems have come to dominate the upper rankings over the years. The top seven spots for mathematics in the PISA 2015 results were all occupied by Asian countries — Singapore followed by Hong Kong, Macau, Taiwan, Japan, China and South Korea.

In PISA 2018, the testing focused on reading in a digital environment and measured trends in reading literacy over the past two decades. It also conducted data on students’ attitudes and well-being.

Little improvement in reading: A PISA press release said one in four students in OECD countries are unable to complete even the most basic reading tasks, meaning that they are likely to struggle to find their way through life in an increasingly volatile, digital world.

Most countries, particularly in the developed world, have seen little improvement in their performances over the past decade, even though spending on schooling increased by 15 per cent over the same period. In reading, Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang (China), together with Singapore, scored significantly higher than other countries. The top OECD countries were Estonia, Canada, Finland and Ireland.

“Without the right education, young people will languish on the margins of society, unable to deal with the challenges of the future world of work, and inequality will continue to rise,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría, launching the report in Paris at the start of a two-day conference on the future of education. “Every dollar spent on education generates a huge return in terms of social and economic progress and is the foundation of an inclusive, prosperous future for all.”

The share of low-performers also increased on average between 2018 and 2009, the last time reading was the main focus of PISA.

Around one in 10 students across OECD countries, and one in four in Singapore, perform at the highest levels in reading. However, the gap between socio-economically advantaged and disadvantaged students is stark: the reading level of the richest 10 per cent of students in OECD countries is around three years ahead of the poorest 10 per cent. In France, Germany, Hungary and Israel, the gap is four years.

States of mind: Student well-being is also a growing concern. About two out of three students in OECD countries reported being happy with their lives, although the share of satisfied students fell by 5 percentage points between 2015 and 2018. In almost every country, girls were more afraid of failure than boys. One in four students reported being bullied at least a few times a month across OECD countries.

When it comes to social and emotional outcomes, the top performing Chinese provinces/municipalities are among the education systems with most room for improvement.

In one-third of the regions that participated in PISA 2018, more than one in two students said that their intelligence was something they could not change much. PISA says these students are unlikely to make the investments in themselves that are necessary to succeed in school and in life. Even if the well-being indicators examined by PISA do not refer specifically to the school context, students who sat the 2018 PISA test cited three main factors that influence how they feel: life at school, their relationships with their parents, and how satisfied they are with the way they look.

However, some countries have shown a remarkable improvement over the past few years. Portugal has advanced to the level of most OECD countries, despite being hit hard by the financial crisis. Sweden has improved across all three subjects since 2012, reversing earlier declines. Turkey has also progressed while at the same time doubling the share of 15-year-olds in school.

Reading a ‘waste of time’: The latest PISA findings also reveal the extent to which digital technologies are changing the world outside school. More students today consider reading a waste of time (+ 5 percentage points) and fewer boys and girls read for pleasure (- 5 percentage points) than their counterparts did in 2009. Teachers’ enthusiasm and stimulation of reading engagement were the teaching practices most strongly associated with students’ enjoyment of reading. PISA found that students spend about three hours outside of school online on weekdays, an increase of an hour since 2012, and 3.5 hours on weekends.

Science and maths: Around one in four students in OECD countries, on average, do not attain the basic level of science (22 per cent) or maths (24 per cent). This means that they cannot, for example, convert a price into a different currency. About one in six students (16.5 per cent) in Beijing, Shanghai, Jiangsu and Zhejiang (China), and one in seven in Singapore (13.8 per cent), perform at the highest level in maths. This compares to only 2.4 per cent in OECD countries.

Equity in education: Students performed better than the OECD average in 11 countries and economies, including Australia, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Japan, Korea, Norway and the United Kingdom, while the relationship between reading performance and socio-economic status was weakest. This means that these countries have the most equitable systems where students can thrive, regardless of their background.

Principals of disadvantaged schools in 45 countries and economies were much more likely to report that a shortage education staff affected their teaching standards. In 42 countries, a lack of educational material and poor infrastructure was also a key factor in stunting success in the classroom. Other countries show that equity and excellence can also be jointly achieved. In Australia, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, Hong Kong (China), Japan, Korea, Macau (China), Norway and the United Kingdom, for example, average performance was higher than the OECD average while the relationship between socio-economic status and reading performance was weaker than the OECD average. Moreover, one in ten disadvantaged students was able to score in the top quarter of reading performance in their country/economy, indicating that poverty is not destiny. The data also show that the world is no longer divided between rich and well-educated nations and poor and badly educated ones.

However, it remains necessary for many countries to promote equity with much greater urgency. “While students from well-off families will often find a path to success in life, those from disadvantaged families have generally only one single chance in life, and that is a great teacher and a good school. If they miss that boat, subsequent education opportunities will tend to reinforce, rather than mitigate, initial differences in learning outcomes,” says PISA.

Gender gap: Girls significantly outperformed boys in reading on average across OECD countries, by the equivalent of nearly a year of schooling. Boys overall did slightly better than girls in maths but less well in science.

Girls and boys have very different career expectations. More than one in four high-performing boys said they expect to work as an engineer or scientist compared with fewer than one in six high performing girls. Almost one in three high performing girls, but only one in eight high performing boys, said they expect to work as a health professional.

Not without criticism: PISA has been criticised for its standardised testing methods, including the setting of the test questions and the way the student samples are assembled. It has been charged with spurring short-term fixes in education systems rather than long-term change that will take decades to occur. Its range of measurements has been called narrow and detracts from less measurable goals such as moral, physical and artistic development.

OECD has also been accused of pursuing a commercial agenda with PISA with regard to

companies and schools offering products such as tests and teaching materials for better scores.